All artists are influenced by the previous generation of artists. Westerns were part of John Carpenter’s cinematic diet growing up. John Ford, and Howard Hawks, these filmmakers were shaping cinema at the time, stamping out a movie language that would become the standard for anyone wishing the tell a story using cinema.

A fan of horror and science fiction movies such as The Thing from Another World and Forbidden Planet, John Carpenter defined another set of standards for a new generation of filmmakers. The modern horror genre is partly his offspring. Like his predecessors, Carpenter mastered the long game, building the tension until the big payoff.

Nowadays, it’s clear that motion pictures have devolved somewhat. Big-budget Hollywood blockbusters lack most of the qualities that gave movies from the past the greatness they deservedly earned. Nowadays, even B-grade movies are more pathetic than ever. Low-budget productions are missing the mark completely.

It’s as if the current batch of filmmakers has stopped learning from the best.

John Carpenter, like his musical compositions, is a back-to-basic, simplicity is the best approach to storytelling. His movies may have been hit and miss at the box office, I certainly put most of these down to budgetary restraints and timing; sometimes audiences are not ready for a certain kind of movie experience; but each of his films has merit and is entertaining, even decades later.

Dark Star (1974)

Despite the student-style, low-budget aspect of the film, what Carpenter achieves here is a certain gritty realism. The characters’ motives, and how they’ve degenerated into bored nihilistic crew members, make sense. The plot is driven by the characters. Even the AI and Bomb-20 have a certain personality that adds to the unfolding drama.

The alien is a ridiculous-looking beach ball thing, yet the director and actor manage to turn it into a menace by employing a mix of frustration, comedy of errors, and ingenious use of a corridor to deliver the element of danger of a bottomless shaft. The ending is bleak, avoiding cliques yet still delivering a satisfying conclusion in tune with how the characters were set up.

Assault on Precinct 13 (1976)

Was influenced by Hawks’ Rio Bravo (1959) and Romeo’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), both siege movies, and has gone on to influence the way action films have been shot and edited ever since. Modern gun battles and depictions of violence from Die Hard to The Matrix owe a lot to this movie. It’s one location, isolated and under siege by an insane gang of killer hoons.

Halloween (1978) Halloween II (1981)

Basically single-handily kick-started the slasher horror films of the eighties and nineties. It’s the boogeyman brought to cinema audiences and with it the template for filmmakers working within the slasher genre.

The sequel is the Carpenter’s desire to push the story into the realm of the unknown, turning the crazed killer into some unstoppable supernatural force. He also falls back on the isolated location technique having the whole story play out in a hospital.

The Fog (1980)

Want to make an atmospheric horror flick with a twist of the supernatural, then this flick has plenty of elements to learn from; building tension, ghostly cinematography, and ghost-zombie sieges.

Escape from New York (1981)

You can see how The Warriors (1979) use of location and design influenced Carpenter, and from here on you can list every post-apocalypse/dystopian movie that had taken cues from Escape from New York. A burnt-out decrepit urban landscape, punk rag wardrobe, hyper-attitude dialogue, and as far as anti-heroes are concerned, Snake Plissken – modelled on Sergio Leone’s ‘Man with No Name‘ – has most likely fathered nearly all anti-heroes since this film.

The Thing (1982)

Ahead of its time in terms of storytelling, having pushed the boundaries of in-your-face gore and un-abating tension, audiences weren’t ready for the gritty realism, the honest dialogue and the intense graphics.

Yet this is his best work.

Authenticity in the setting makes the fantastical horror that emerges later more intense. The banter and truthful reactions from the characters, the gore, these work if executed in the way Carpenter has done here.

Also, The Thing showcases the pinnacle of practical effects*. But Carpenter’s team, never rely on just the latex and puppetry, they incorporate lighting, camera angles and editing, and the cast’s reactions, to bring the horrors to life, and they do it well.

A study of this film is a must if a director really wants to get under the audience’s skin.

*Shame they didn’t allow the team behind The Thing (2011) to showcase their practical effects, instead the monster work was covered up with CGI.

Christine (1983)

How do you bring an automobile to life? Well, there’s Herbie, from The Love Bug series, and there’s Christine.

Here Carpenter succeeds with Christine whereas many filmmakers adapting books consistently get it wrong. Not only is Christine a good adaptation of Steven King’s book, but it is also an improvement of the source material. Carpenter discards the irrelevant parts of the book and captures the essence of the story, visualising it for the big screen. This should be a basic rule for adapting books into movies.

This is how it’s done.

Starman (1984)

With Starman, the genre plays out in the background, while the cast takes the centre stage. Carpenter allows the characters, Jenny and her alien husband, to evolve.

Telling their story is the plot, and that’s a good takeaway because when you have the plot based around action set-pieces or gimmicks, you’re likely to end up with boring trash. The audience has to care about the characters, otherwise, the film is an empty period of time filled with purposeless spectacle.

Big Trouble in Little China (1986)

You’re tasked with bringing an action-heavy mixed-genre motion picture to the screen. Let Jack Burton guide you.

Even when the fight choreography and effects spectacles drive the plot, it still requires likeable characters to link it all together. The protagonist is flawed and balanced out with the supporting characters. Jack is the hero, yet Gracie and Wang do a lot of the heavy lifting ‘and thinking,’ because he’s willing to risk everything to help the good guys (albeit reluctantly) he’s given the credit. A unique anti-hero of sorts, not seen very much in modern cinema.

Prince of Darkness* (1987)

Evil entities, zombie sieges, isolated scientists, the blending of science and the supernatural, bleak urban setting, jump scares, building tension, and effective practical effects, this film combines all of the elements that make Carpenter’s movies entertaining. He’s at his best here, pulling no punches, so if you use this one as a study guide, it covers it all.

They Live (1988)

There was never any heavy politics in Carpenter’s work, he just worked in themes such as the boogeyman is gonna get ya, never fuck with the supernatural, and that totalitarianism can be bad yet bad-ass as well.

Here, however, Carpenter dives right into the fray, basically directly accusing the elites of this world of colluding with the enemy, in this case, aliens. I guess that’s why I ended up seeing this at a small indy cinema at the edge of town, the establishment wasn’t too pleased so they squashed this film and seemingly, his career.

Yet, this is how to make a social statement that echoes well into the future, (look at how our society is mimicking this world thirty years later). You need to be direct, have good one-liners and plenty of action, and be as honest as possible.

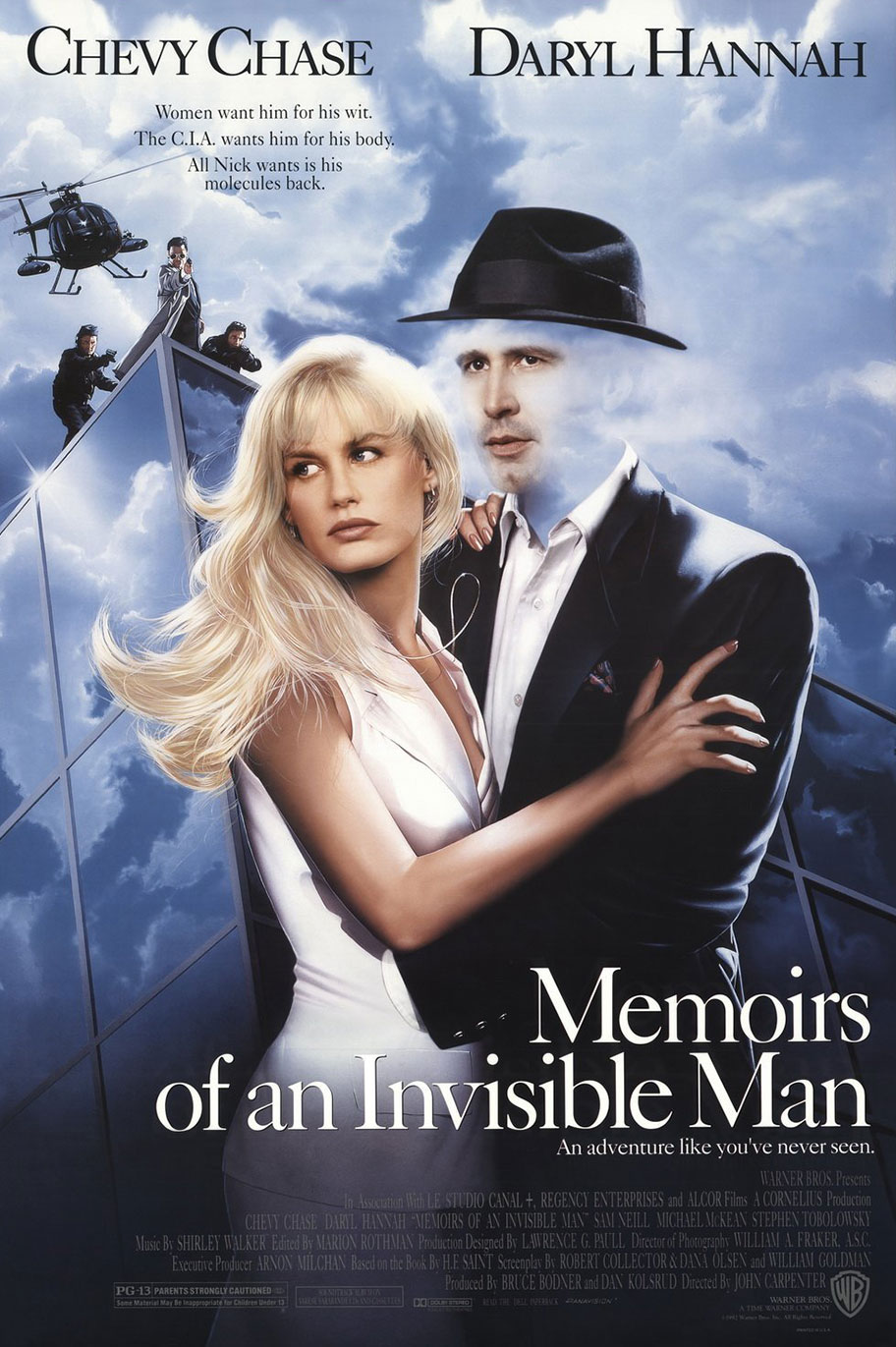

Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992)

Pressed to do a paycheck-genre film? Here Carpenter ticks as many boxes as he can. He gets the effects and action right, they still look good to this day. The story takes its time, building it up as it progresses.

The Invisible Man has been around since H.G. Wells created him. The Universal films of the 1930s had the effects down pretty well. So do your research, stay true to the genre and keep the story centred on the protagonist. Carpenter does this here and what we got is a film still entertaining decades later.

In the Mouth of Madness* (1994)

Bending reality. Just when you thought one couldn’t pioneer and blend genres any further, Carpenter does it again. Again, inspired by two previous masters of horror, H.P Lovecraft and Steven King, this film is a goldmine of Carpenter’s cinematic techniques.

Village of the Damned (1995)

Got a remake to do? Carpenter’s rule number two; don’t change or mess with the original source material. It’s ridiculous how remakes are drastically different from the origins. That’s why they suck. If you’re going to force in a different concept, make a new movie, don’t squat on the brand name.

Escape from L.A. (1996)

Rule #3. If you’re going to remake one of your own films, and can’t be stuffed working out a new story to tell or direction to take your anti-hero, then go with the original script, tweak it a little, and call it a sequel.

The thing is with John Carpenter, even when shackled with a limited budget and technology, he sure doesn’t shy away from being ambitious. Do the same film today, with the same budget and script, and you’d easily sell earthquakes and surfing a tsunami to Snake Plissken fans.

Vampires (1998)

Combining genres? Having read the book before watching the film adaptation, it was the first time I got to see The Carpenter’s choices play out. Again, he takes the coolest aspects of the novel and morphs them to fit his own mythology. What’s interesting, John Steakley’s 1990’s Vampire$ reads as if it’s been heavily influenced by Carpenter, complete with zombie/ghoul sieges and a bleak ending. The choices made are kinda understandable considering he wanted to make more of a western, but…

…take away the vampire element, this would be the type of western he would make.

Ghosts of Mars (2001)

John Carpenter rips off his own work here, gratuitously and shamelessly. The whole film is a catalogue of his techniques, and while it doesn’t come together at all, it does help to identify them. You can recognise aspects of every one of his films, from visuals, action choreography, story, and motifs, right down to the outright cheese.

The Ward (2010)

Ten years on, Carpenter sticks to what he knows best. Jump scares, gritty isolated settings, ghost stories, paranoia, all typical Carpenter, and it was competing in an age where horror movies are massively influenced by him.

The Carpenter’s Film Language

John Carpenter’s directing style masterfully blends an array of distinctive elements, creating a cinematic experience that is both unique and deeply influential. His films often navigate the realms of horror, science fiction, and action while incorporating the following recurring motifs and techniques:

1. Gritty Setting

- Carpenter frequently sets his stories in rough, unforgiving environments—whether urban decay (Escape from New York), isolated outposts (The Thing), or bleak small towns (Prince of Darkness). These settings contribute to a grounded, visceral feel that immerses the audience.

2. The Slow Build-Up of Tension

- He masterfully stretches suspense with patient pacing, allowing dread to creep in before explosive moments of horror or action. Halloween is a quintessential example, where Michael Myers’ looming presence is felt long before the chaos begins.

3. Siege by Hordes of Zombies/Possessed

- Carpenter excels in crafting siege scenarios, with characters barricaded against overwhelming, otherworldly threats, such as the zombified cultists in Prince of Darkness or the possessed townsfolk in The Fog.

4. Unstoppable Killer Stalkers

- Carpenter’s villains often feel invincible and implacable, such as Michael Myers in Halloween or the shape-shifting alien in The Thing. These antagonists evoke existential dread and an unrelenting sense of danger.

5. Ghostly Atmosphere

- Films like The Fog create a supernatural ambience that blends eerie visuals with Carpenter’s chilling soundtracks, crafting environments where spirits and malevolent forces loom.

6. Criminal Anti-Hero

- Carpenter’s protagonists are often morally ambiguous, like Snake Plissken in Escape from New York. These characters possess charm and grit, making them both relatable and unpredictable.

7. A Lurking Alien Horror That Possesses/Takes Over Individuals

- The alien in The Thing embodies Carpenter’s fascination with body horror and paranoia, as it takes over hosts and destroys trust within the isolated group.

8. A Grim Sense of Paranoia

- Themes of distrust and betrayal run through many of his films, especially The Thing and They Live, reflecting a worldview where appearances deceive and allies turn against each other.

9. Evil Ghost Possession

- Ghostly possession is a recurring theme, such as in Christine, where a car is inhabited by a malevolent spirit, or The Fog, where vengeful spirits attack the living.

10. Infectious Madness

- In In the Mouth of Madness, Carpenter delves into Lovecraftian horror, where the spread of insanity becomes as much a threat as any physical antagonist.

11. Comedic One-Liners

- Despite the dark tones, Carpenter injects humor through sharp, memorable one-liners, often delivered by anti-heroes like Jack Burton in Big Trouble in Little China.

12. Big Fight Scene

- Carpenter stages exhilarating fight scenes, like the iconic alley brawl in They Live. These sequences balance intensity with a touch of absurdity.

13. Big Gun Battles

- Action-packed gunfights are a staple in Carpenter’s work, from the police station siege in Assault on Precinct 13 to the chaotic battles in Escape from New York.

14. Isolated Group Fighting to Survive

- A recurring theme in Carpenter’s films involves small, isolated groups—such as in The Thing or Assault on Precinct 13—banding together to fend off relentless external threats.

15. Strange Politics

- Carpenter often critiques societal structures, as seen in They Live’s anti-capitalist themes or Escape from New York’s dystopian vision of a militarized society.

16. Unusual Casting

- Carpenter frequently casts unconventional actors, like Kurt Russell transitioning from Disney star to action hero, or wrestler Roddy Piper headlining They Live. This lends his films a distinct edge.

17. Lovecraft Homages

- Carpenter’s films often evoke H.P. Lovecraft’s cosmic horror, especially in The Thing and In the Mouth of Madness, where the unknowable and unfathomable terror drives the narrative.

18. Gruesome/Gory Practical Effects

- Carpenter is a champion of practical effects, with The Thing showcasing groundbreaking gore and creature design that remains a benchmark for horror filmmaking.

19. Western Elements

- His films often borrow tropes from Westerns, such as lone gunslingers, standoffs, and rugged anti-heroes. Assault on Precinct 13 and Escape from New York exemplify these influences in a modern setting.

These are just a few, there are more examples, many having been incorporated as standard in most genre movies. The point is, don’t just copy The Carpenter, instead innovate, create new cinematic languages, and learn from the best whether it be Carpenter or any of the great masters before him.

Discover more from Bill Kandiliotis

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.